Demolition by neglect’ fells historic Miami building long designated for protection

One of the oldest standing commercial historic landmarks in Miami-Dade County, the 122-year-old DuPuis Medical Office and Drugstore in Little Haiti, has been demolished after partially collapsing.

Though the long-vacant 1902 building, best recognized for its sidewalk arcade, has been a protected historic site since 1985, the city of Miami’s building official ordered what remained of the structure torn down on an emergency basis for safety reasons after two sections of the roof fell in on January 8.

The collapse and the demolition, begun by the city eleven days later, shocked historians and preservationists who for years have been awaiting the DuPuis building’s promised restoration as a prominent piece of the planned Magic City Innovation District, a giant redevelopment scheme that would create a high-rise mini-city in the heart of Little Haiti.

While the Magic City developers say they will build a replica of the building, it won’t be on its original footprint as they intended. A ruling by Miami-Dade County that has baffled preservationists means any replica will have to pushed back well off the street front the original building occupied. The replication and move are factors that preservationists say may diminish the historic value of the site.

“Here you have a significant historically designated building in area where very few historic buildings still exist, and a developer apparently willing to do the right thing, and yet this happens,” said a frustrated Christine Rupp, executive director of Dade Heritage Trust, the county’s largest preservation group. “It’s going to take me a little while to wrap my head around whether a rebuilding even makes sense here.”

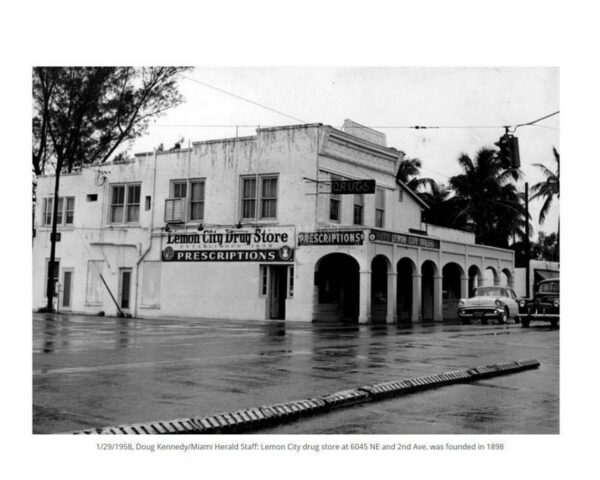

Considered the most significant historic landmark in Little Haiti, the building was erected by Dr. John DuPuis, one of Miami-Dade’s most prominent early physicians, as a medical office, pharmacy and home in what was then the farming community of Lemon City. Until its demolition, it was the only recognized surviving building from Lemon City’s rural origins, and the oldest one north of downtown Miami made with concrete.

Its demolition comes at a fraught time for historic preservation in Miami-Dade. The movement is credited with saving a once-dying Miami Beach and helping reverse the decline of the city of Miami.

But a backlash driven in part by developers and uber-wealthy property owners has recently brought about the loss of some of Miami-Dade’s most significant homes and buildings, including mobster Al Capone’s Miami Beach mansion, as well as the likely burial by developers of an ancient indigenous site in downtown Miami and a continuing threat of sweeping state legislation that overrides local protections for historic and architectural landmarks and districts.

A restoration deal in 2019

The tale of the DuPuis building’s downfall involves changing neighborhood fortunes, intense development pressure, and city and Miami-Dade agencies working at seeming cross-purposes.

The proposal for a massive upscale complex of apartments, shops and offices in the middle of one of Miami’s poorest neighborhoods prompted an uproar that took months of public meetings and negotiations to settle.

The city approvals in 2019 required Magic City’s developers to restore or reconstruct the DuPuis building, which sits on Northeast Second Avenue just south of 61st Street. Renderings released by the developers when they applied for development permits display a gleaming, restored DuPuis building flanking the main entrance to the development.

The developers say the structure, unoccupied for decades, was already in a state of severe deterioration and too far gone to be saved when they bought it in 2014. Though they spent $50,000 to shore it up after the acquisition, project partner Neil Fairman says it required a total reconstruction or a full replication. Only one wall was sound enough to stand up, he said, and his group has been warning the city that it was in danger of failing.

But Fairman, a principal with Plaza Equity Partners, complained their efforts to rebuild it have been stymied since 2017 amid bureaucratic wrangling with the city and Miami-Dade County — which blocked the reconstruction of the structure on its historic site.

The county highway division’s reasoning: That the historic building’s columns and arches, built in the typical fashion of the day, violate current rules because they covered the public sidewalk — an architectural detail cited in a 1985 city report as one of the reasons it was declared a historic landmark in the first place. Usually, buildings designated as historic are grandfathered in.

But instead, in a final May 2023 memo to the city, the chief of the county highway division, Leandro Oña, ruled that since the structure had to be rebuilt anyway, it should be torn down and reconstructed somewhere else to meet modern setback requirements. County rules prohibit buildings from impinging on a public right of way, the letter says.

Fairman said the developers were still hoping to get city support to reverse the county ruling, but had been unable to get a hearing before the city’s historic preservation board to publicly discuss options, and were still trying when the building’s second story caved in. City preservation staffers told the developers they were too shorthanded to tackle the issue, Fairman said.

“We were willing to rebuild the building where it was,” Fairman said. “We even did plans for it. We were trying. God knows we tried.”

City attorney Victoria Mendez, in an email in response to questions from the Miami Herald, said she would review the setback question with the city preservation officer, calling it an “interesting issue.”

Emergency demolition

City spokeswoman Kenia Fallat, also in an email response, said the city had no choice but to demolish the structure once its south-side and arcade roofs fell in. Though homeless people sometimes sleep in the arcade, she said there were no known injuries.

Citing “demolition by neglect,” Fallat said the city obtained an emergency demolition order. The demolition now means the developers are in default of their development agreement with the city and must submit plans to replace it for approval of the historic preservation board.

Faiman said they have every intention of doing so, but still hope they can rebuild on the original site since part of the building’s significance was its period architecture and the sidewalk arcade. He also said that it would have been advantageous for the developers to rebuild the original on site because preserving it would mean significant tax benefits.

“We would have liked to keep it. We just couldn’t do it,” he said, noting that consultants took laser measurements and made 3D scans of the original building so they can replicate it fully. ’We’re still standing by that.”

Fairman and his partners paid $15 million for the DuPuis property and the adjacent and far larger former Magic City campground and trailer park in 2014.

Though the developers have renovated and leased numerous warehouses on surrounding properties they amassed in Little Haiti, new construction has yet to start. Work to install underground utilities is starting now, and the developers hope to begin construction on the first piece, a residential high-rise, later this year. Fairman said he can’t say when the DuPuis replica would be built until the city preservation board considers the plan.

Preservationists said they find the county’s position on setbacks unreasonable in light of the building’s historic import, which relies in part on the arcade over the sidewalk at the street’s edge.

“That’s the whole point of preserving the architecture of the building,” Dade Heritage’s Rupp said, laying the blame on the loss of the building partly on the fact that the city has had seven preservation officers in eight years, counting interim appointments. “This situation is indicative of what happens when there is a lack of oversight and lack of communication between departments and government agencies and extreme turnover in city staffing. There is not appropriate staff to monitor properties, but no one’s going to take the blame for this.”’

If the developers can salvage some of the original materials and details from the demolished building to use in their rebuilding, Miami history blogger Casey Piket said, there would still be some historic value in the project even if it’s moved back significantly from the sidewalk. He noted that the historic Overtown wood-frame home of Miami’s first Black millionaire, D.A. Dorsey, was fully rebuilt at least once because of extensive damage.

“It’s strange that the county is digging its heels in,” said Picket, who writes the miami-history.com blog. “There’s value to where the building was located. But if you’re replicating and moving it back from the sidewalk, and hopefully there are some fixtures or aspects of the building that you could include, I would say there is value to that.”

But Shawn Wilt, vice president at Magic City Properties, the property owners, said in an email that the city has taken control of the site, is not allowing the developers access and has said it intends to clear all the rubble and building remnants away.

A building with rich history

Rupp and Piket say DuPuis was a significant figure in early Miami history, establishing the first medical practice and pharmacy in Lemon City, an unincorporated farming area that was annexed the growing city in the 1920s, and helping establish what eventually became Miami Edison High School. DuPuis and his family at first lived upstairs before building a home nearby.

The doctor also started a dairy farm to improve the nutrition of local farming families, among other civically minded ventures. His family continued running the pharmacy for at least a few years after DuPuis’ death in 1955, though it’s unclear for how long, Piket said

By then, Lemon City had been subsumed by the city and become urbanized. The neighborhood declined in the 1970s as residents flocked to the newly developed Miami suburbs, and began attracting Haitian refugees fleeing the oppressive Duvalier regime. Since then, the neighborhood has been better known as Little Haiti.

The DuPuis family continued using the building in some capacity into at least the 1980s, according to the designation report prepared by the city preservation office in 1985, but was eventually vacated and fell into progressively worse shape. Once the Magic City group took possession, Fairman said, an engineering consultant determined there wasn’t much of the original that could be saved. The building materials, chiefly wood, oolite limestone and concrete with no steel supports, were crumbling.

Rupp and Piket said it’s hard to know who to blame for failing to stop the building’s deterioration, but that someone should have acted much sooner.

“It goes back to the fact that the city can designate it historic, but they don’t put any obligations of upkeep on the owners, which is why demolition by neglect is a popular way of getting rid of a building you don’t want,’’ Picket said. “If you let it sit there 10 years, asking ‘what did you do about it?’ is a valid question.”

What is not in question was that the DuPuis building, and the arc of history it represents, was worth saving, Rupp said.

“DuPuis wasn’t just a nobody,” she said. “Let’s pay tribute to the man, the culture. Buildings tell stories. They tell stories about people. This is a piece of Miami, and what these pieces of Miami can do, in a city that is continuing to evolve, in a place where so many people trace their personal histories to other places, is that they allow us to have a shared sense of history.”

This story was originally published January 24, 2024, 5:30 AM.